How Codebase Structure Shapes System Predictability

[software-development programming software-architecture software-engineering Why does the structure matter?

In one of the previous posts, I discussed the influence of coding conventions on software development. Now I would like to elaborate on gains of having a well-structured codebase.

The structure of the codebase should visually communicate the main functionalities and responsibilities of the system. This at-a-glance understanding helps developers, new team members, and stakeholders quickly grasp what the software does and how it’s organized. A well-structured codebase is like a well-organized library. It allows developers to quickly locate specific pieces of code, modules, or functionalities. This ease of navigation reduces the time spent searching and promotes efficient development and debugging.

The structure of files in a codebase not only indicates the system’s responsibilities and complexity but also imposes a certain order onto the future development and evolution of the software. This is because a well-defined structure sets the foundation for how the codebase should continue to be organized and extended over time. It plays a significant role in guiding the development of a software system by indicating rules, patterns, and design principles.

The straightforward design of the codebase brings predictability for developers. In user experience design, predictability ensures that users can anticipate how the user interface will respond to their actions. This creates a more intuitive and user-friendly experience. Similarly, in a well-structured codebase, you can anticipate how different components interact, what restrictions specific layers have, where to find particular functionalities, and how changes in one area might affect others.

The chaotic structure is one of the reasons why the system becomes obscure. Obscurity directly relates to system maintainability. In a system where information is not obvious (e.g. we must dive into the code deeply and reverse engineer it to determine the external dependencies that the system relies on), maintainability is becoming an issue over time. Modifications are made slowly and without confidence, increasing the risk of errors and degrading overall efficiency.

In the following sections, I would like to discuss a few cases of codebase ordering (or disordering).

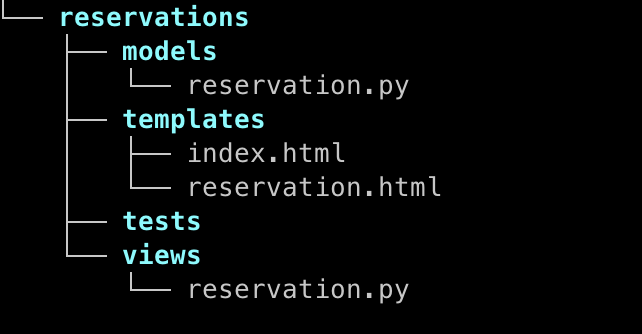

Model-View-Template

R. Martin, in his great article Screaming Architecture, claims that the codebase should reflect the business use cases that the system promises to deliver. I agree with that conviction when we are facing a quite complex domain. However, if we have a simple web application or CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) service, following the framework conventions could also be a bearable option.

The simplest approach in web development is to use the Model-View-Template pattern (implemented by frameworks like Flask, Django, etc.), where:

-

Model layer that is responsible for domain logic and persistence.

-

View is a place where application API is defined. The view orchestrates application logic by interacting with the model and executing requests to external services.

-

Template is a presentation layer (e.g. HTML templates) that handles the User Interface part.

As the complexity and dependencies of a system grow, the limitations of this pattern may become apparent. Here’s why:

-

Complex Business Logic: In more complex systems with intricate business logic and a multitude of dependencies, MVT might struggle to provide the necessary structure and organization. It can lead to large and unwieldy views, making the code harder to manage.

-

Dependency Management: Complex systems often involve various external services, databases, and libraries. MVT doesn’t inherently address complex dependency management or integration challenges.

For complex systems, it’s essential to consider the trade-offs between simplicity and scalability. In such cases, adopting a more flexible and modular architectural pattern that allows for better management of complex business logic and dependencies may be a wise choice.

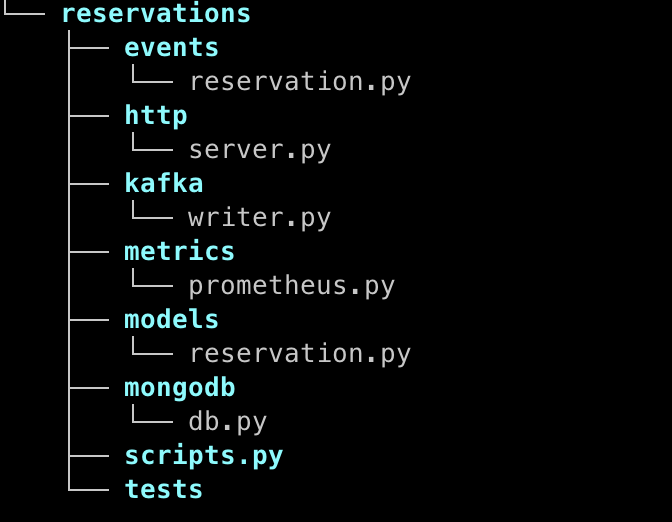

Chaos

It’s common for developers to default to a chaotic structure when they are unsure of how to evolve from a simpler approach like the MVT pattern. The easiest way is to keep everything at the top level where all components seem to have the same significance (which usually is not true).

At the very beginning, that approach could be tempting because this structure is not overwhelming. However, it is really difficult to say what this application is responsible for. We only know that it implements a kind of reservation model. The application logic is probably implemented within HTTP server controllers. We cannot distinguish layers that have properly defined boundaries. With the absence of clear boundaries, it is really difficult to impose any rules or constraints on code development. As the codebase grows and complexity increases, chaotic structures hinder scalability and adaptability to changing requirements. Developers working in chaotic codebases often experience cognitive overload (usually extraneous) due to the constant need to navigate through disorganized code and make sense of it.

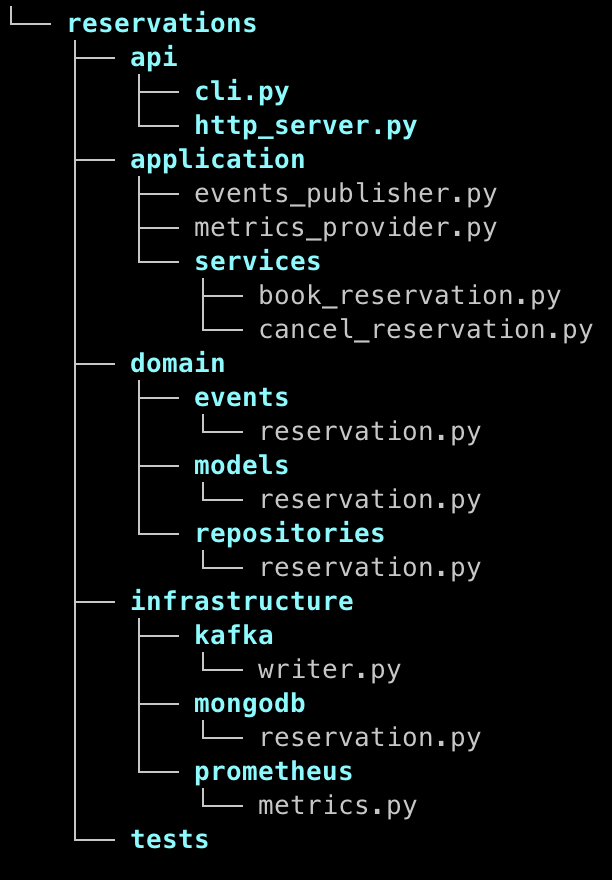

DDD-like layers

The layered architecture, suggested by Eric Evans in his Domain-Driven Design fundamentals book, offers a structured and modular way to manage complex business logic and dependencies. Here’s a breakdown of the layers:

-

Domain Layer: This layer encapsulates the core business logic, domain models, and business invariants. It’s where the heart of the application resides and ensures that business rules are consistently enforced.

-

Application Layer: The application layer orchestrates and coordinates the execution of business processes by interacting with the domain layer. It’s responsible for handling use cases, transactions, and workflow management. What is really important, it should be free of knowledge about infrastructure.

-

Infrastructure Layer: The infrastructure layer manages external dependencies and resources such as databases, external APIs, and services. It provides the necessary infrastructure for the application to function, including data access and communication with external systems.

-

API / Interfaces Layer: This layer serves as the entry point to the application, providing various interfaces for interaction, such as HTTP APIs, command-line interfaces (CLI), or messaging interfaces. It exposes the functionality of the application to external clients and users.

The core functionalities of the service are represented by the application layer. We can see there that our system should provide two business features: booking a reservation and canceling a reservation. To determine how complex is the solution, we can look into the infrastructure layer and see how many dependencies we have.

This approach allows us to have a set of conventions that will drive the development. Some examples:

-

Retrieve and save data only within application services using repositories. This makes our code clean of ad hoc data flushes to the data store.

-

Do not contaminate application logic with transport API concepts, e.g. request, cookies. This makes our services transport agnostic. The same application logic can be reached by HTTP REST endpoints, CLI scripts, or event handlers.

-

and so on…

This application design, inspired by DDD and layered architecture, is particularly effective in domains where complex business rules and invariants need to be enforced. It is also helpful in services that share the same application logic between several entry points to the system.

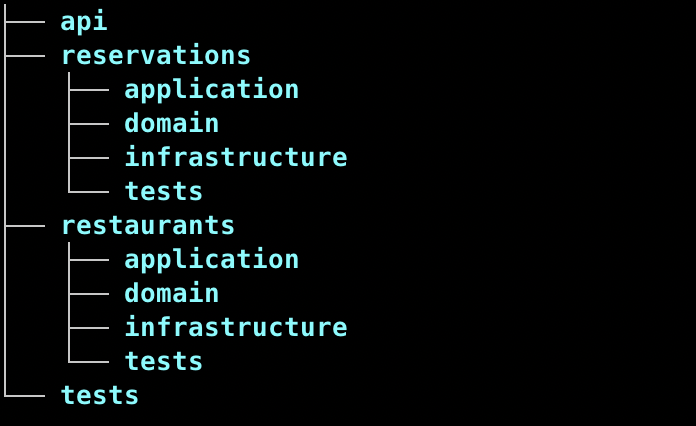

This strategy may be successful when our system consists of more than one subdomain.

One of the options could be sharing an api layer but each subdomain can have a separate set of application, domain and infrastructure layers.

Conclusion

Although some developers might believe that a codebase’s structure or design can emerge naturally over time, this approach often leads to problems (chaos leading to the “broken window” problem). Having a provisional design that determines the initial structure of a codebase is valuable, even if it’s not set in stone. An upfront design provides a starting point and a roadmap for the codebase. However, the design should be flexible enough to accommodate changes and refinements as the project progresses. We should also be ready to change the structure entirely due to radical changes in functionalities or the architecture revolution. There are situations when we have to throw away the ladder that we used to climb up to where we are. However, it does not mean that we should not commit to the specific structure because we probably need to refine it or abandon it in the future.

While a well-structured codebase is just one aspect of software development, it is indeed a low-hanging fruit that can bring substantial gains in terms of maintainability, efficiency, and overall software quality. By addressing codebase structure early and maintaining it throughout the development process, teams can set a strong foundation that makes it easier to tackle other complexities and challenges that may arise during a project’s lifecycle.