Efficiency traps

[efficiency productivity books life Efficiency can be defined as doing things correctly, but also in a reasonable amount of time. We are trying to improve our work attitude and are ready to disturb our work-life balance to generate more output. To boost our efficiency we tend to eradicate activities that do not increase the amount of desired stuff done. Cannot make a break, need overtime, must finish X, can have a desk lunch, etc. Constant efficiency growth becomes the main goal. Something that should be instrumental is becoming essential.

In this post, I would like to consider some dark sides of efficiency and why should we be careful about it.

Efficiency definition

Efficiency at the simplified level can be defined by the following equation:

We take the assumption that Effort is the total properly(!) done output delivered by a person, while Time is the time slot when the effort was made. As it stands, there are two ways of increasing the above factor. Either by producing more output within a given time slot (option 1) or by decreasing the time slot span with the effort scope maintained (option 2). Although we have two options, they both usually end up with more “global” output produced. Even if we decrease the time slot needed for tasks (option 2), time slots gained are used for new activities.

The above definition can be called objective one. There is also another interesting perspective. When we assess someone’s efficiency, we rarely have access to information on how much time the given effort has taken. We usually see only the effect of it - generated output.

I call it apparent efficiency.

People can hide the amount of time preserved for duties to make an impression of efficiency growth. From that perspective, we can “increase” efficiency by overworking ourselves instead of improving the work process.

We are done with the definition. Now I will turn to cases when efficiency growth can get us into trouble.

Efficiency spiral

In his inspirational book Four thousand weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Oliver Burkman claims that optimization and efficiency growth usually generate additional work. As a result, an efficiency bump often extends our to-do list.

Of course, there is no issue that we want to work better or faster. The problem starts when boosting efficiency becomes the main goal of our activity. In that situation, we are feeling enjoyment mostly from increasing the tempo of our work. It can create a spiral that leads to a crash. At some point, you cannot speed up or even keep the tempo, so the main source of your enjoyment (boosting efficiency) vanished. If you cannot find an alternative that brings enjoyment, you probably experience burnout. To avoid the spiral we should treat efficiency instrumentally, and care more about effectiveness.

Effectiveness vs Efficiency

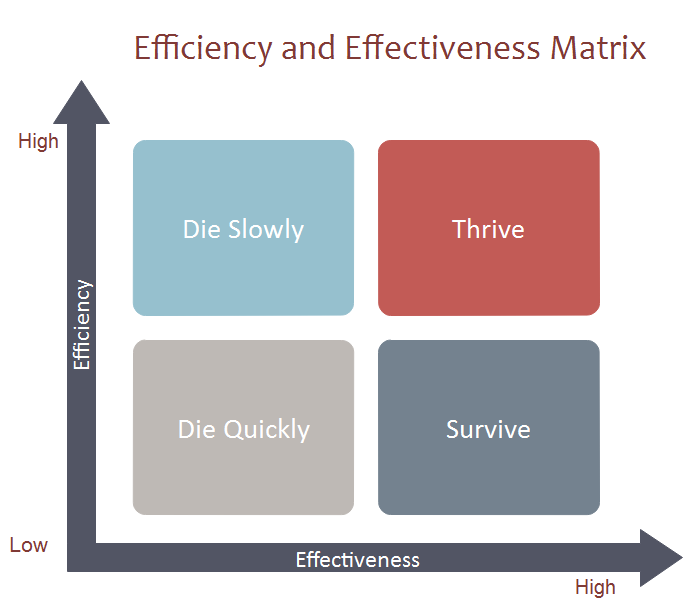

The root cause of the aforementioned spiral is that we tend to confuse effectiveness with efficiency or treat them as synonyms while they are essentially different concepts. Effectiveness is responsible for goal-setting and decision-making. It is at a strategic level. As far as efficiency is concerned, it is only an implementation instrument, a tactical tool. You are effective when taking proper direction(s). Following the direction in the right way is the efficiency domain.

You probably can discern the difference by the following example. When people’s career success is analyzed, you can find a lot of people that were great at school but do not fulfill their potential in the job market. Individuals that do not have problems with efficient work are usually great at school because they do not take decisions about what has to be done. They have supervisors and teachers that set the direction, and the best pupils follow it diligently. The situation is entirely different when you must choose your major at university or a job position. The proper implementation is not enough when your chosen field of interest is not profitable or you can hardly find a job. Although you mastered something, it is not desired by the current market. Your decision was bad or unlucky, and great efficiency cannot change your plight.

source: https://www.edrawsoft.com/efficiency-effectiveness-matrix-templates.html

Another example is the Scrum Sprint approach. Nobody denies that the velocity of a development team is an important factor in sprint success. But it is only instrumental for a sprint goal. We are inviting problems when our main focus is to deliver more story points than we have in the previous sprint instead of thinking about what outcome we want to achieve when we complete the current iteration.

Efficient stagnation

Efficient stagnation is a situation when we stay in our comfort zone only because we want to do our duties more efficiently. We are doing the same or similar tasks, but are crazy about doing them faster. So we abandon new challenges and are not interested in broadening our horizons, because all energy is put into increasing the tempo of current repetitive activities.

Breaks underestimation

Our efficiency dream can represent a situation where each minute of our working time is utilized productively. We do not spare time for futile activities like breaks, socializing meetings, or midday naps. We have an ideal working day without unnecessary “disruptions”. In his interesting book When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, Daniel Pink believes that this approach usually strikes back both short-term and long-term efficiency. Our focus and concentration run out during mental activity and to keep sharpness we have to recharge quite often (mini break every hour). Good breaks can be really refreshing and improve our performance:

-

social break - talking to co-workers is a good way to improve mood and reduce stress

-

tech-free outdoor break - leaving phone or laptop aside and having a walk can increase motivation and concentration

-

naps - properly done (10-20 min) can improve cognitive performance, boost mental and physical health

Each person has a different dynamic throughout the day. We have a peak, trough, and rebound time. It is a really good idea to find when is your peak and place the most intensive task in that time while taking a long break when you know your performance naturally drops.

Conclusion

I have presented four different issues that can be side efficiency traps. It is definitely a good idea to step back occasionally and consider what it means to have meaningful work instead of boosting efficiency at all costs.

At the very end, I would like to leave you with a great quote to remember:

“There is nothing so useless as doing efficently that which should not be done at all”

P.Drucker