Deep work. Essentialism in asynchronous culture

[learning deep-work communication books productivity Deep work

Nowadays, we are getting accustomed to working in a continuously interrupting environment. Smartphone notifications, hundreds of e-mails, open spaces, and meetings slicing our workday. We are feeling busy, and overworked, but are we more productive? If I am a salesman or project coordinator that way of working can bring good effects and even improve my skills. However, for Software Developers, Designers, and other professionals that need a quiet environment for creative effort, it can lead only to frustration and burnout. They need something that is called deep work. Deep work is a concept popularized by Cal Newport in his book under the same title published in 2016. The author divides mental activity into two categories:

- shallow work, that does not need intensive concentration like sending e-mails, formatting documents, chatting using communicators, etc.

- deep work, that demands distraction-free focus on one task like writing a document, learning a new skill, designing a software system, etc.

Switching contexts and multitasking is intrinsic for shallow work, while deep work needs a time slot that is uninterrupted for a reasonable amount of time. Sometimes, it could be challenging to determine whether a given activity is rather shallow or rather deep. To tackle it, Cal Newport suggests an intelligent graduate criterium. It is a kind of mind experiment you carry out to find how much time a quite smart person needs to complete the task. For example, If you need to build a machine-learning model that can respond to natural language sentences, you have to in the ideal scenario take some classes in the Artificial Intelligence field or even complete a computer science degree. Hence, that task has definitely deep nature.

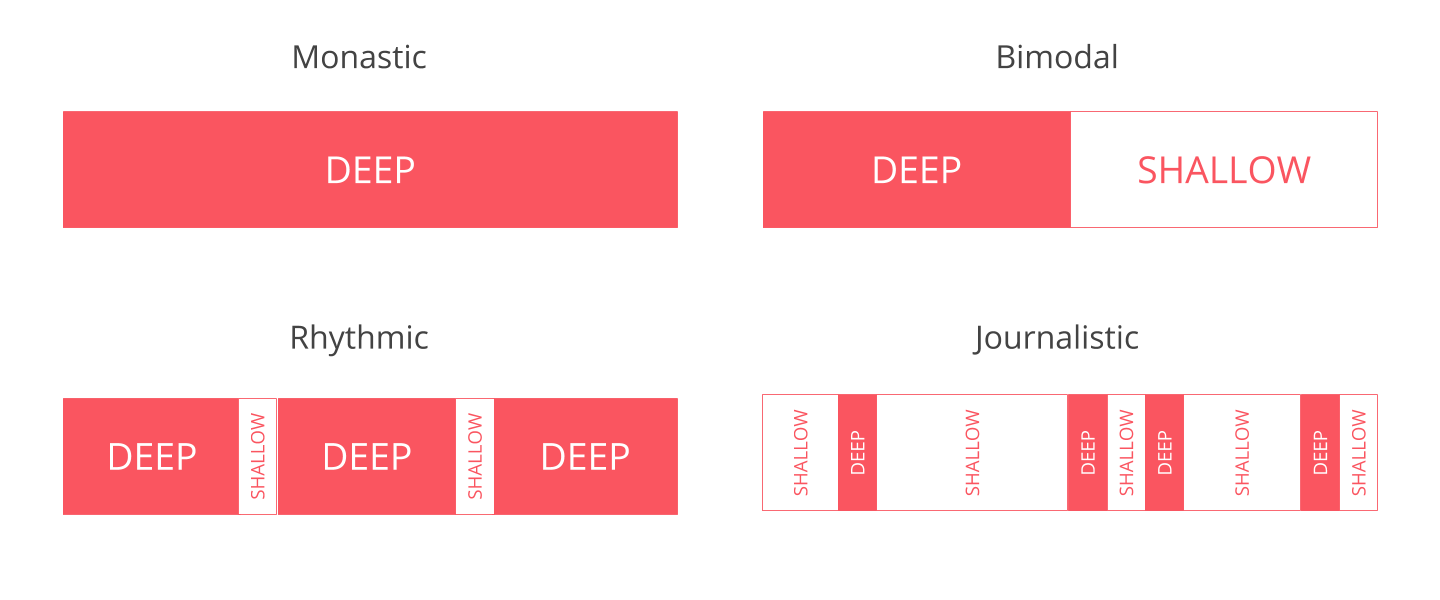

As far as deep work is concerned, it can be performed in four different modes:

- monastic, you are closed to the external world, do not have an e-mail address, do not check your smartphone all day long, and you work uninterrupted all the time.

- bimodal, you work monastically by part of the year, month or week, e.g. you go to a mountain shelter for the whole winter, you close your office for people each first week of the month, etc.

- rhythmic, you have a scheduled workday with some time slots reserved for distraction-free work.

- journalistic, whenever it is possible, you turn to short-term deep work.

source: https://blog.nuclino.com/slack-is-not-where-deep-work-happens

source: https://blog.nuclino.com/slack-is-not-where-deep-work-happens

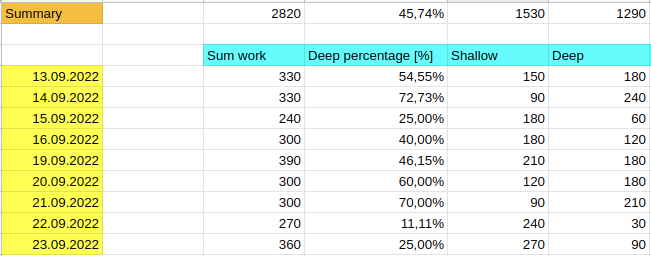

Monastic and bimodal modes are rather reserved for professions that can manage work without intensive communication with people, like writers, scientists, researchers, etc. Journalist mode fits best to people that are experienced with deep work and can easily switch into that state. From my experience, the best option to start with deep work is the rhythmic mode. You can schedule your workday by dividing it into 30 min time slots, trying to find 2-3 periods lasting at least an hour each for deep work. Personally, I do that scheduling just before my workday starts using a google spreadsheet (for each day, I have a table with deep work, shallow work, and rest time columns). If I know that I have some meetings, I try to reserve shallow time for them. The plan is flexible, of course. It’s not necessary to be obsessive about it. Nevertheless, when it is possible, you should adhere to it. The main guideline is that a deep work slot cannot be interrupted (no e-mail inbox checks, smartphone turned off or silenced, no Slack / WhatsApp / Messenger chatting) and should be focused on a single topic.

This method of tracking is one of my habits that make possible to measure how much time I preserved for deep work. After a week, or month I can evaluate whether I am satisfied with the amount of it or not, and maybe I should change something in my approach.

Deep work can bring us a lot of gains. So, why is it so hard to make some space for it? There are, in my opinion, two primary causes: the first is internal, and the second is external.

Essentialism

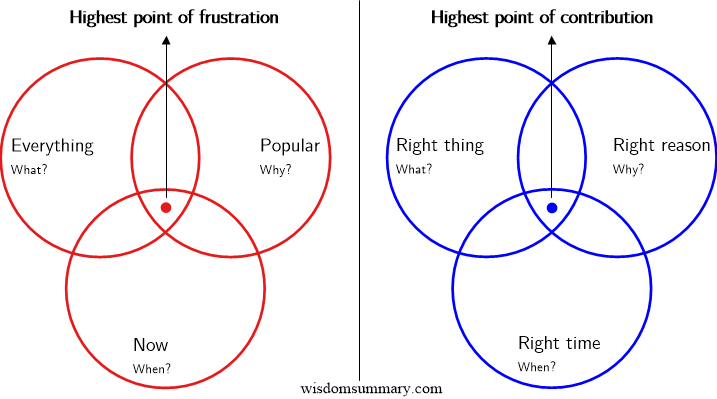

The root of the internal cause is an inability to distinguish between what must be done and what may be skipped or put off. People frequently focus on efficiency (completing as much high-quality work as possible in a given amount of time), leaving effectiveness (completing the right things) under-addressed (I have written about it also here). We cannot do everything, so the only way to be successful and do not feel overworked is to assess and choose only essential options. It is the ability to say ‘no’ when we know that something is not worth our time, or we simply do not have enough time to do it in the right way, even if it is a tempting opportunity. “If something is not definitely ‘yes’, it is definitely ‘no’”. This is the leading idea of Greg McKeown’s great book Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less that I strongly recommend reading. The author tries to convince us that a trade-off is an intrinsic part of our life and we should take the approach of determining where is our highest contribution point. To do it, we sometimes need to slow down or make a step back to get a better perspective. We do not get deep work slots in our workday by default, but only by design. Eisenhower matrix is a quite popular tool that helps assess available options and determine what is really important.

source: https://wisdomsummary.com/a-summary-of-essentialism/

source: https://wisdomsummary.com/a-summary-of-essentialism/

Asynchronous culture

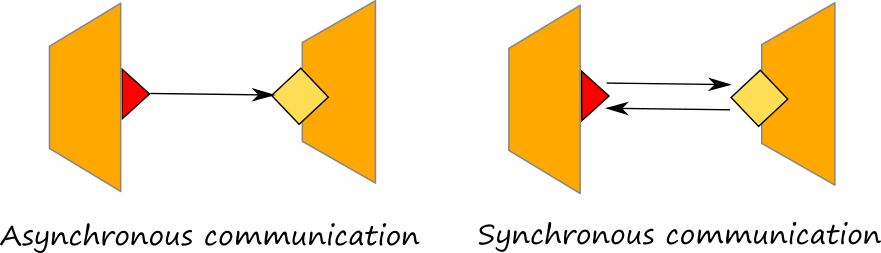

The other source of our difficulty to find a space for quiet, calm, and uninterrupted activity, is the workplace environment. We have to be in touch with our workmates, be responsive to our customers, report to managers, etc. The question is whether our organization for sure demands from us this real-time communication all the time. A lot of companies, try to implement asynchronous communication by default (see a dropbox example with “at your own pace sessions”). This approach is based on pushing information rather than pulling it:

- writing my daily status on Slack instead of gathering my team for a short meeting,

- creating good documentation and runbooks, to avoid unnecessary request about how something work, or what should I do in case of emergency (this is a great post about the culture of writing),

- preparing an agenda before a meeting and a summary after it. The agenda gives people an introduction to the topic, while the summary usually allows for avoiding follow-up meetings or calls with people that missed the event.

source: https://docs.jolie-lang.org/v1.10.x/language-tools-and-standard-library/architectural-composition/synchronousvsasynchronous.html

source: https://docs.jolie-lang.org/v1.10.x/language-tools-and-standard-library/architectural-composition/synchronousvsasynchronous.html

Asynchronous culture brings people autonomy and lets them improve their skills and work effects. Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson in their book It doesn’t have to be crazy at work share some experiences of how they introduce a company culture that respects creative effort:

- meeting slots, if the meeting is necessary can only be scheduled in a given period of time, e.g between 10 a.m and 1 p.m.

- library rules in a workplace, even if you work in an open space you can behave as if you are in a library (calm, quiet),

- eventual response, you can ask a question to your workmate, but do not demand an immediate answer.

Changing organization is of course much harder than changing your personal habits. However, you can suggest some improvements gradually. If they work for the company, the resistance will not be strong and persistent.

Conclusion

To conclude, you must protect your time and do not let it be (un)designed by chance and other people. The crucial thing is to find the proper balance between satisfying communication and creative effort.